Prof. Ajayakumar / Indian Painter

It can be said of Kerala that it is a peculiarly unique region for having illustration art and a community that appreciated it. The prevalence of literary magazines and popularity of literature were important factors that facilitated the overwhelming acceptance of illustration art as a version of painting by Malayalees. For about seventy years or more, Illustrations kept pace with literary merit and played a decisive role in how literature got presented. The popular acclaim enjoyed by those who practice illustration art within Kerala has helped create both critics and blind fans. One has to only examine the flawed reasoning going into pronouncing and writing that the beauty of illustrations surpassed the text of ‘Randaamoozham’ to realize how much a section of our society cared for illustration art. We should also disregard the counter argument that illustration art was meant for those without creative talents. It goes without saying that the fundamental vision and backdrop of a story or novel belongs to the writer. A gifted illustrator undertakes a tour through the backdrop and vision driving the narrative and attempts a painterly interpretation. The fact that Kerala had such illustrators who were adept at these interpretations expanded on the art’s acceptance.

In the 1930s when M. Bhaskaran began illustrating for ‘Sanjayan’, he was faced with block printing technology and an informal artistic background. His humorous illustrations of crowds of human figures, facial expressions, their local variants etc. are as refreshing today as it was then. He was succeeded by K.C.S. Panikar whose story illustrations for ‘Jayakeralam’ magazine later led to what has since become ‘Ideal models of Kerala style illustrations’. Illustration art sojourned various golden periods of literary fiction through the likes of M.V. Devan, A. S. Nair, Namboothiri, C.N. Karunakaran etc. and represented the realist, modernist traditions by means of line art. It isn’t inconsequential trivia to be having such artists who in their work unraveled illustrations of a century’s life in this part of the world including people belonging to diverse regions, various caste and religious groups, attire, different geographies etc. (novels like Smarakasilakal, Shakthi, Ntuppuppaakkoraanendaarnnu, Khasakkinte Ithihaasam, Pokkattadikkar, Yayati, Randamoozham etc. and hundreds of stories for example). Namboothiri’s appropriation of Classical Indian Architectural conception of human physiology for ‘Randaamoozham’ and the immaculate physical grace that encompassed A.S. Nair’s illustrations of ‘Yayati’ were of a sublime order.

Against this backdrop, one speculates that may be Chandrashekharan’s illustrations represent a thematic distinction. This writer’s reflection along these lines was spurred by a comment to this effect by P. Surendran in his lecture delivered on the sidelines of the exhibition.

Chandrashekharan’s illustrations saw the light of day in Deshabhimani weekly. Deshabhimani was different from other publications with regard to its political orientation, commitment and unique literary beat. Chandrashekharan’s art was presented with narratives molded out of this political dogma. It indeed cannot be ignored that the magazine’s ideology (to borrow a phrase by P.Surendran) may have shaped and charged the thematic framework of the illustrations. It is only natural for the illustrations to acquire a political context when you extensively illustrate for stories or novels that thematically tackle social divisions and conflict viz. inequality, torture, rights based protests, power centres, multitudes of people, agonizing hospital settings etc. It should be noted that the specialty of Chandrashekharan’s illustrations are more pronounced in his handling of the aforementioned thematic contexts. If we study the repetitive tropes in Chandrashekharan’s illustrations of the last twenty years like people and women who get hauled or tortured at the hands of the law keepers, poor and destitute children, people driven to society’s margins, beggars etc., we will get to see the ‘ideology’ of the magazine surely revealing itself. Through consistent engagement with core themes, he has acquired enough dexterity to handle any situation or human figures. We should remember that basically it is the writer who ‘dictates the topic for the illustrator’ and again it is the publisher who decides on the length of time required for the completion of the creative process. Any sense of freedom enjoyed by the illustrator equals the illustrator’s experience of freedom between the writer and the publisher. It is only natural that Chandrashekharan’s hand, perfected over a long period of time oscillating between both frontiers, had to be repetitive. The reason for this has got nothing to with Chandrashekharan but with the language of illustration itself, which has undergone several experiments and evolutionary reiterations in its history. In this regard, his turn towards computer graphics deserves special mention.

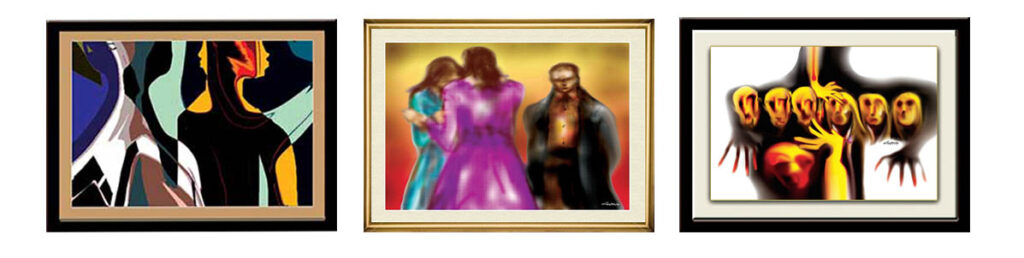

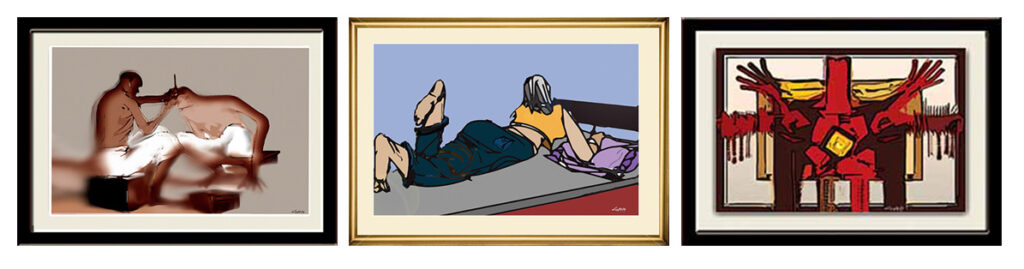

Thematically speaking, Chandrashekharan’s computer-aided works address contemporary political developments. It is only at this topical level that these works compare with his early illustrations. In relation to the impersonal images of Gujarat riots and Marad, these works are animated by an endeavour to infuse detailing and human likeness. When an illustrator ventures into another medium, it is very likely that he/she would anchor his visual framework to that of line art. With reference to Chandrashekharan’s computer imagery, the lines are not only conspicuous by their absence in the end result but the figures also transcend the structural confines established by the lines. Attainment of balanced composition alongside boundaries easing into each other merits our interest. Chandrashekharan has reached a stage where he recalibrates the possibilities of Photoshop technology to suit drawing-based imagery but with no indication of drawing whatsoever. In these images, we witness visual language playing with the effective interplay of light and shadow and the blurring of different locales and shapes.

Curious it is to ask why these works do not dwell on several other manipulations plausible on a computer generated work. The illustrator composes the illustration in accordance with the vertical character of the page. Vertical compositions are indeed a salient feature of our illustrations. The human shapes in the works of Namboothiri and Chandrashekharan are perfect examples. This writer suspects that it is because of Chandrashekharan’s acutely alert illustrator’s instinct that he would not employ horizontal composition or resort to stretch or spread or elongate in ways that is eminently feasible on a computer. However, figures constructed by spreading and dissolving the boundaries of the shapes onto the surface seem to expand from the confines of illustrations into the realm of painting. If the exhibition of his works were to be curated under precise mediums, it would have been more interactive and thought provoking.

In a formal sense, Chandrashekharan’s computer imagery can be grouped under two classifications. Those adhering to precise boundaries which resembles figures made out of paper cutting and others that dissolve the borders into the picture surface. His illustrations for Babu Paul’s ongoing service story in ‘Madhyamam’ are great examples for border-bound geometric figures and plain colour combinations.

When an illustrator becomes a painter, he creates strictly within in the structural framework of line art. In effect as the illustrator applies colour here and there between the lines, colour tends to lose its structure and the subsequent composition generated of lines and colours together look as if they agree and disagree both at the same time. The water colour works of Chandrashekharan lauded by P. Surendran was the product of a crisis like this. One can only consider them as initial applications of tinted colour on line art that did not make use of water colour’s surface level potential or colour composition. The most exciting factor however is that through computer-aided works, Chandrashekharan has been able to transcend such limitations and basic features of colour combinations. Though many contemporary artists in India are experimenting with computer graphics today, it seems to be a provisional exercise. And most of them rely on computer generated picture archives. Their works are also devoid of the tangible quality of image making by an artist. Therein lies the excellence, goodness, potential and truth in Chandrashekharan’s computer-aided illustrations.

Deshabhimani Weekly